Self-motivated, self-starting individuals are incredibly motivated to find their weaknesses. It’s not far-fetched to say that some of us actually seek to make ourselves perfect — rational, calculating beings making the right type of decisions at just the right times. But we’ve learned from Star Trek; we don’t look to eliminate emotion either and turn ourselves into Mr. Spock. We want just the right amount of emotion in our lives.

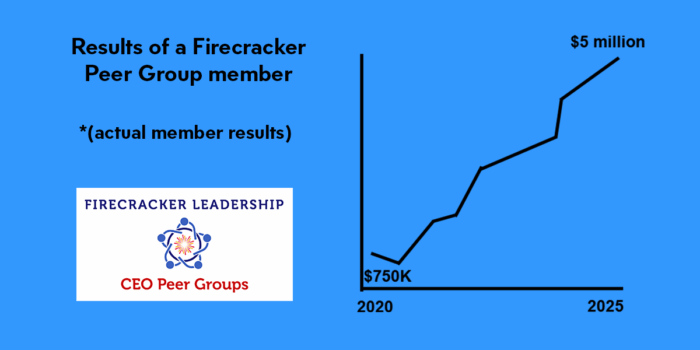

People often overestimate what they can accomplish in one year. But they greatly underestimate what they could accomplish in five years.

— Peter drucker

If we’re night owls, we seek to become early risers. (Ben Franklin did it!). If we’re procrastinators, we look to become doers. If we’re always late to meetings, we look to be early to meetings. We want to eliminate our weaknesses and become a little More.

This is, of course, a laudable goal. But the self-starters among us have probably all run into the same problem: We don’t actually follow through on the things we know will make us better. We don’t eat the broccoli. We get a little too robotic. We get up at 8:30 when we said we’d do 5:30 from here on out. We leave that essay until the last second even though that was never going to happen again. We’re five minutes late. We don’t become lore at all, and the failure to get there makes us feel like less.

The culprit is the thought that any important change happens quickly. It doesn’t matter whether you’re trying to get up early or pick up and implement the Psychology of Human Misjudgment. Anything important happens slowly.

From Potential to Useful

And why should it be otherwise? If you were to truly understand, in-depth, and apply the Psychology of Human Misjudgment to your dealings, you’d be way far out ahead of your peers and your former self. The advantage of understanding human nature is incredible. But it takes deep, repeated study and a long gestation period to get there. It takes applying the ideas to the world, feeling them out, forgetting them, re-doubling yourself, and trying again. Not giving up when you forget or fail. It is through the process of refinement that one learns new habits and ideas.

The visual mental model I like for self-improvement is imagining something like a Lathe.

A lathe, for the non-engineer, is a tool that molds a piece of material into some shapely form. A machinist would use a lathe to take a hunk of metal and turn it into a usable engine part, for example. The lathe takes something with potential and shapes it into something useful by slowly refining it and shaving away the excess.

Compounding works in other areas besides money.

The way I think about it, if I can get 5% wiser and better every year, then I will be about twice as wise as I am now in less than 15 years. (Go ahead, grab your calculators.) In less than 30 years, my return will be 4x. This is how the non-gifted among us can surpass otherwise more intelligent people.

Tiny Improvements, Massive Results

Tiny improvements add up to massive differences.

Compounding works in other areas besides money. And we want to compound worldly wisdom.

These little mental tricks like the Lathe and the idea of 5% yearly improvement are just ways to remind myself that I’m not going to wake up wiser/nicer/healthier/smarter tomorrow morning or the morning after. And just as importantly, if I backslide on a goal I’ve set or I forget something I thought I’d learned well, that it’s really not the end of the world. I don’t need to give up and call it hopeless. All I have to do is figure out where I slipped, re-double my efforts, and go after it again. All I need is 5% a year to become 4x better in my adult lifetime.

The truth is that whatever bad habits you have or whatever things you’re struggling to learn, there’s probably a good reason. Your biology and your experiences to date have set you in stone to a certain extent, and the older you are, the more likely that is to be true. The chains of habit are too light to be felt until they are too heavy to be broken. Billion-dollar industries have been built on convincing you that it’s easy to make big changes or to get a lot wiser and better. But it honestly isn’t. It’s hard work.

Yet any study of great individuals reveals that the work is worth doing.

So just imagine if you could make slightly better decisions every year. Whether it’s 5% better consideration of all of your decisions, or making 5% of your decisions differently, or some permutation thereof, it doesn’t really matter. Every year you’ll look back at some part of your old self and wonder how you could’ve been so dumb. And one day, in less than 30 years, you’ll look back and see your old self as almost unrecognizably stupid.

What more could you ask for?